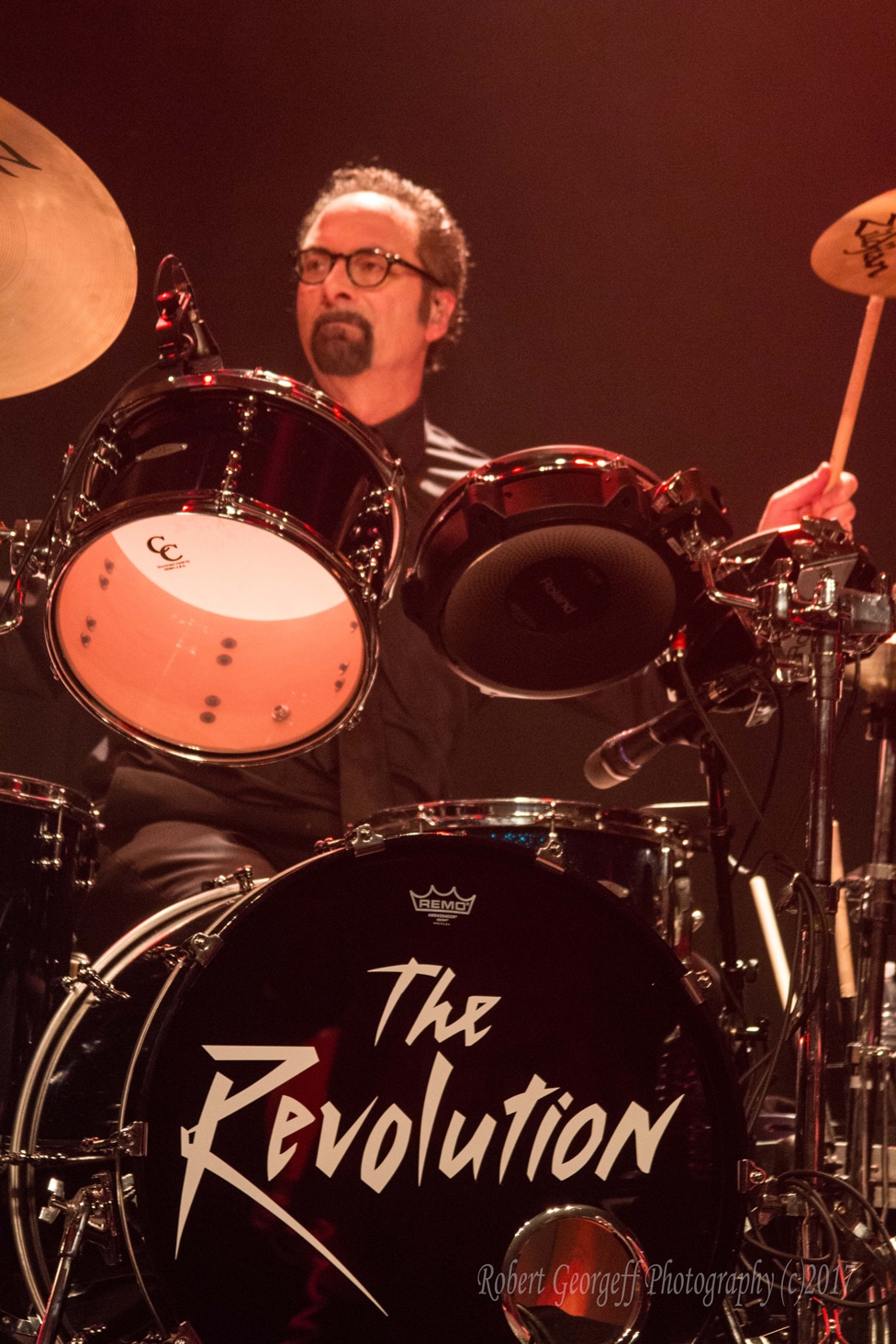

If there’s one drummer who you could say had the best job in the business, it would be Bobby Z. of Prince’s band, The Revolution. As Prince’s drummer from the very first concerts in 1979 until 1986, Bobby Z. sat on the throne of The Revolution from the beginning, when Prince rescued him from, as he recalls it, “a normal life to be with him on his trip to the outer regions of the solar system.”

In an interview with Guitar Center on the eve of the fourth anniversary of Prince’s passing, and ahead of the airing of “Let’s Go Crazy: A Grammy Salute to Prince,” for which Bobby Z. reunited with The Revolution for two special performances, the drummer discussed his storied career with Prince. The Minneapolis native opened up about his start with the Purple One in the late-1970s, when they were both, as he says, still “unfamous.” From those earliest days, to the fateful 1981 gig in L.A. opening for The Rolling Stones, to the making of the landmark Purple Rain and 1999 albums, Bobby Z. offers a unique perspective into Prince's transformation from mere mortal into one of the greatest entertainers in the world.

“It was a ferocious approach to a show,” said Bobby Z. on Prince and The Revolution’s live performances. “Learning how to attack it and just being in total command of not only the band, but the tens of thousands of people witnessing it.”

Over the course of his 40-year career, Prince worked with a wide array of talented musicians. But there was only one Revolution. Here is a snapshot of those pivotal moments in Prince’s career, and how he took Bobby Z. and The Revolution on his meteoric wild rise to fame.

During the “Let’s Go Crazy: A Grammy Salute to Prince” special, co-musical director Jimmy Jam said that Prince and The Revolution changed the world. How do you feel the band did that with Prince?

My personal journey with Prince starts in 1977, way before changing the world. And it was a step-by-step, brick-by-brick process. But Prince figured out how to get attention—whether by doing something outrageous or not speaking. He was the master, pre-internet, of intrigue. He gave us an intrigue, too. He painted this incredible layer of mystery, but the thing is, we were a band that was later with one of the greatest, if not the greatest, entertainers of all time. So, to back up somebody like that, musically, we had to bring it. It wasn’t just some change the world with a fashion or a look or something superficial—it was his incredible musicality and us rising to the level to have him achieve the stage presence that we all know now is the greatest of all time.

What did you learn from working with Prince?

We were both very unfamous together. First off, I’m extremely grateful that he rescued me from a normal life to be with him on his trip to the outer regions of the solar system. As far as learning, he had centuries of musical knowledge and that was the odd thing. He was almost a different species once he got going. The songs would flow like water. From 1600 Paganini to Mozart, Zeppelin, the Beatles, the Stones, Sly Stone and Cab Calloway—everything was in his knowledge. It wasn't just a normal lifespan of musical gifts. It was an eternal, kind of infinity talent that made him incredibly unique.

How would you describe the sound The Revolution and Prince created together?

As far as Prince’s musicality goes, it just boggles the mind. It really does.

Prince played everything, including the drums. Being that he was a multi-instrumentalist, how involved was Prince in working with you to get the drums sound he was looking for? Did he leave that completely up to you, or did he weigh in on your drum set configuration and tone?

Each song had its own individual blueprint, so some songs you’d just play it and he never gave it a second look. And with other songs, you know, he was a beatmaker. He would pair these iconic beats with iconic melodies—it all went hand in hand. Iconic bass parts on top of iconic lyrics on top of iconic vocals. It was just one layer after another. You participated in that particular song’s structure and sound, or you worked with him, or he did it by himself. Live, of course, became a different animal. You both were focused on recreating the record in the best possible way. I kept my job for 10 years because I could figure that part out. It was expected of you to bring that song to life in its authentic form and you had the tools to do that and that’s what we did.

How did you recreate those iconic drumbeats for the stage?

The Linn LM-1 became synonymous with his electronic drums. I don’t know if people realized, but he was also probably pushing the envelope of having the Linn playable, having pads hooked up to it to play. And that’s what I would do. So even if I played a part that was programmed, it was still the authentic sounds, it was kind of like a [Ford] Model T and it didn’t work all the time. It was early stages, and we had an amazing tech, Don Batts, who built this interface, you know the early days of taking acoustic guitar microphones and triggering drums, it was all pioneering. Prince was a tech pioneer on top of everything else. It was taking these new instruments and pushing them to the limit and beyond.

Is pioneering how you would describe his approach to making music in general? The sound and what he was creating crossed genres, boundaries and borders.

The way I like to describe it is he reaches everyone from the heaviest metal musicians to polka bands. They love Prince. Everybody just seems to love him. Genre-wise, he’s their guy. And rightly so, because he could just cross platforms and genres effortlessly. It was all music to him, and he would just decipher it, whatever came to him.

Let’s talk about Prince and The Revolution’s first Los Angeles gig—opening for the Rolling Stones in 1981—a show that took place during a pivotal time in the band’s career and in the country in general, and one show that hit Prince, only 23 years old at the time, particularly hard.

Everybody’s got a beginning, and that’s why I’m saying the early shows, 1979, 1980, 1981, it was certainly not the universal, iconic guy we all know now. People hear the color purple and they associate it with Prince. It was such a far way back. Audiences were much more rambunctious back then. They were burning disco records at the end of the ’70s. It was pretty crazy when you think about it. Literally burning them. So, music was kind of more tribal. The Stones got it, you know. Mick and Keith, Charlie and Bill and all those guys were consoling us afterwards, but it was a combination of what he was wearing, the “Dirty Mind” vibe and a falsetto voice that might not have gone over well. Fans were also waiting too long in the afternoon. We went on at like 2 p.m. and the Stones didn’t go on until 7 p.m. So, when you’re coming in at 6 in the morning and you’re crammed in the front and there’s 80,000 people there and the show starts, you’re ready for the Stones already. We were just kind of red meat for an alliance of that whole situation. It was just a perfect storm.

Courtesy of the Recording Academy®/ Getty Images © 2020

Courtesy of the Recording Academy®/ Getty Images © 2020

Jumping ahead just a couple years to the recording of “Purple Rain.” The Revolution and Mavis Staples’ performance of the song was a standout during the Grammy special. And, I believe the first time Prince and The Revolution played it live was at First Avenue in Minneapolis (the same venue featured in the film Purple Rain). You also recorded this song for the soundtrack album during the live debut. Looking back, what was that experience like?

August 3, 1983 was the first time we played “Let’s Go Crazy,” the first time we played “Computer Blue,” and the first time we played “Purple Rain.” That recording of “Purple Rain” became the master of the record and, of course, Prince cleaned it up, but still the scaffolding, the framing of the house was built that night. That master goes back to the movie for a lip synch of that performance and then that record comes out. So, these three elements of that song create this triangle of energy, which makes the song kind of alive every time you hear it. When I hear it, I feel like it’s still alive but it’s not, and it’s a part of history but it’s a gospel song. Having Mavis sing that right now, at this moment, gives it a kind of church gospel feel that people so desperately need.

The song is medicine. Music was medicine to Prince. “Purple Rain” is medicine and it’s an amazing experience. I remember vividly. First of all, it was 99 degrees in there and people could smoke freely, so just imagine the humidity and cigarette smoke, and plus the stage smoke. So, it was heavy breathing. He kept saying, you know, "We’re making history, we’re making history," that night. He was pacing like he did in the movie, but in a more excited way. Just hyped up. This is it. And he just kind of got us into a zone that was impenetrable. The whole show, songs like “Electric Intercourse,” which was left off, was just kind of the finest moment in our careers and it’s captured and it still replays in my mind when I hear the song. I’m grateful that that song means so much to people and it’s been described as his sacred prayer, it’s beautiful.

Plus, the guitar solo is just another thing that he takes you to another dimension, so it’s very fitting that that song be played now. It’s him that’s doing that, it’s him that’s telling everybody that somehow this is all going to be okay.

During the special, Maya Rudolph referred to Prince as “the artist forever known as Prince.” Why will Prince and his legacy never be forgotten?

I know he’ll never be forgotten because there’s just nobody like him. By knowing him so closely as I did, and then just comparing him to everyone else I ever met in the world, I can see why he’s going to be remembered. There’s just nobody with that gift of what we had, which was just the speed and brain, the musical IQ. The computer working in his head was like a different species or something. It was just really different. Like da Vinci, Mozart, Shakespeare—he’s one of those people.

Where do you think his creativity stemmed from?

We’re all just our mom and dad’s DNA. The reality is his dad was really talented. His mom was really talented. But there’s something about what he did, going back centuries. There’s some way that he’s reaching back to Cab Calloway and Mozart and Elvis and the Beatles and the Stones and Santana, Earth, Wind and Fire, Grand Central Station, Larry Graham. It’s all kind of in his knowledge, and being a bandleader just became natural to him once he figured it out. That’s the mystery, isn’t it? Because I mean we were really unfamous in the beginning, and the caterpillar was a metamorphosis that became his butterfly. That’s the only way that I can describe it. What makes a caterpillar turn into this beautiful flying creature? He went through a metamorphosis in front of my face. The gifts grew at an unbelievable rate, and the gifts were songs. Songs are the currency of the music business and his songwriting, I think—to answer your question on why he will be remembered forever—it’s his ability to compose.

Several songs were also performed off 1999, one of the first Prince albums to feature The Revolution. How do you think that album stands out against others in the Prince catalog?

I think the lead from Controversy to 1999 was the leap. And that’s ironically after the Rolling Stones show. After that defeat, he kind of realized well, if I’m going to be a superstar, I’m going to need these people. So, then it was like, okay well I’ll go this way, and there was “Little Red Corvette.” The word “party” also was not a controversial word, but it belonged to a bygone era now, and the fact that in “1999” when he says party, it’s kind of tongue-in-cheek. He knew exactly what he was doing. He was getting the rockers with the corvettes and he’s got levers left in the R&B market with “1999”—he’d achieved the double fork in the road and now he was crossing over and that’s what 1999 did. It crossed him over completely. He kind of freaked people out with 1980’s Dirty Mind, a ton of people didn’t understand. It was really based on what was going on in London. He was fascinated by Steve Strange and Siouxsie and the Banshees, and Adam and the Ant and all that stuff. And Controversy was just kind of a mirror. Am I black or white? Am I straight or gay? And then 1999 was, well, him saying, “I got it. I figured it out here we go.” And then it was never looking back.

Do you have a favorite Prince song to play?

For me, it goes way back. There’s two, kind of bookends. One is “Just as Long as We’re Together.” Off the first album. There’s a great drum fill, kind of similar to “Take Me With U.” Kind of a big tom fill. And then, of course “Purple Rain.” As a little drummer growing up—I started at 6, 7 or 8 years old—and to be on a record that’s thought of on that level is humbling to say the least.

What was it like to perform “Purple Rain” more than 35 years later during the Grammy Prince tribute concert?

I thought it was important then, but I think it’s really important now. To do it four years later, after his passing, after all the history. Everything was meaningful, and I hope people get that heaviness and importance of it that we definitely are proud to do it for everyone. It’s a holiday.

It’s very apropos that Prince is the last show as we know it, the big tribute taped with a big audience show. Now that we’re living in this new world, it’s going to be a while before we see one of those again. And it’s Prince and it just kind of makes me smile that his power is still to bring everyone together in a way that hasn’t happened in weeks or months now.

.jpeg)