It all started because of Bill Nelson.

I interviewed the Be-Bop Deluxe guitarist for the San Francisco fanzine Musician’s News before the band’s April 15, 1978, concert at Winterland with The Jam and Horslips. Nelson was one of the first British artists to release an independent album (Northern Dream, 1971), and he was also a very early disciple of home recording, which made him and Pete Townshend my heroes of DIY music production.

By then, I had my hands slapped constantly for the audacity to reach for a mixer fader in professional studios, and I was desperate to take matters into my own hands as the 1980s unfolded. Nelson’s Echo Observatory in his Yorkshire, England, cottage became my inspiration, although I couldn’t afford the Fostex A-8 reel-to-reel 8-track deck (approximately $2,220 USD in 1981) he built his studio around.

What to do?

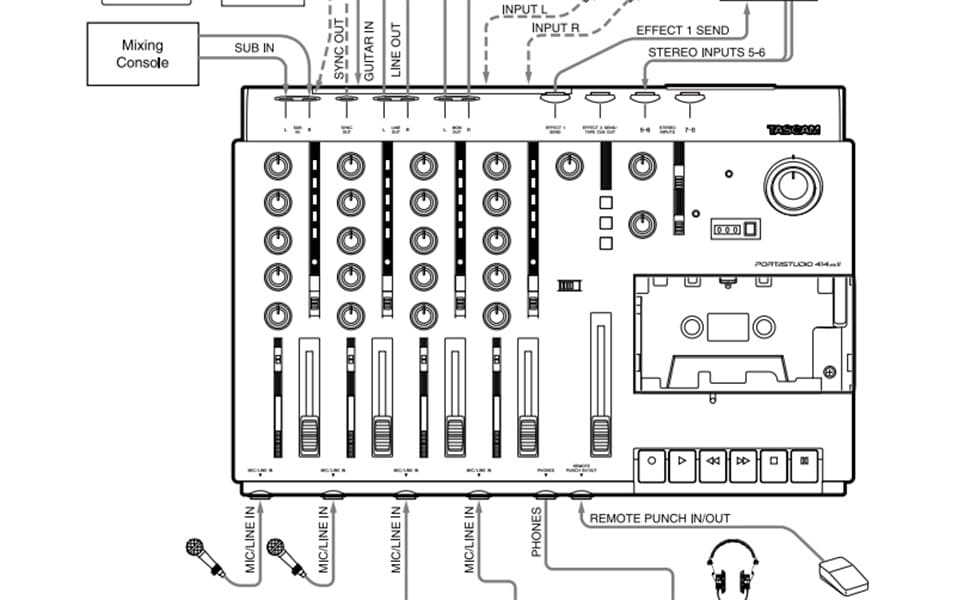

Pictured: TASCAM Portastudio 424 MkIII Cassette Deck

The "Beatles Tape Bounce" Inspired a Home Studio Blunder

But first—a sad tale of an epic fail. Around 1977, emboldened by The Beatles bouncing between reel-to-reel 4-tracks to assemble the majesty of Sgt. Pepper’s Lonely Hearts Club Band (1967), I attempted the truly ridiculous.

I bought a used Technics RS-263 top-load cassette deck, two Radio Shack microphones and a Realistic (Radio Shack) SCT-11 front-load cassette recorder to attempt my own “bedroom version” of multitrack recording.

It was liberating and fun and educational. It also sounded horrible.

Pictured: TASCAM Portastudio 414 MkII Routing Diagram from Original Owner's Manual

Even using high-quality chromium-dioxide tape and activating Dolby B noise reduction on the decks, a few bounces spawned hurricanes of audible hiss. When I proudly played one of my homegrown multitrack productions in the dash-mounted cassette deck of my dad’s prized Cadillac DeVille, he accused me of breaking it. (“My Rusty Draper tape doesn’t sound like that!” he yelled.)

Unless I raised the thousands of dollars required to create and experiment in professional recording studios, it appeared my production career was doomed.

The TEAC 144 Kicks Off the Home Studio Boom

I couldn’t believe my eyes. Everything I wanted for my home studio dream was staring right at me from an advertisement in a long-forgotten music magazine.

Introduced in 1979, the TEAC 144 Portastudio offered four tracks, a basic integrated mixer, simple controls, actual faders, and a readily available and inexpensive tape medium—cassettes. At a retail price of $899, the 144 wasn’t exactly cheap, but the Guitar Center on Van Ness Avenue in San Francisco offered enough of a deal that I could make one mine.

For me and so many others, the TEAC 144 was a truly seismic moment in DIY recording.

Pictured: TEAC 144 Routing Diagram from Original Owner's Manual

After all, few musicians could manage the expense, installation and setup of multitrack tape decks, mixers, patchbays, monitor systems and all the goodies offered by pro studios from large facilities to neighborhood 4- and 8-track dens. But the 144 had almost everything you needed in a compact package. You could establish a home studio in any room of your house by just adding a microphone and some headphones for monitoring.

No one had any illusions you could use a 144 to craft audio quality close to that of Zenyatta Mondatta (The Police, 1980), Boy (U2, 1980) or Crimes of Passion (Pat Benatar, 1980), but the deck could produce relatively clean and extremely vibey demo recordings. That was good enough. Musicians finally had some power in the world of audio production—and that potential would increase exponentially in the coming years from the advent of the Alesis ADAT Modular Digital Multitrack (1991) to today’s DAWs.

Bruce Springsteen and a TEAC 144 Crush It With a Platinum Album

Well, there was perhaps one artist in the ’80s who may have had illusions a cassette multitrack could deliver a mainstream hit. Between the end of 1981 and the spring of 1982, Bruce Springsteen used a TEAC 144 Portastudio to record demos for a planned E Street Band album. The sessions commenced in the bedroom of Springsteen’s Colts Neck, New Jersey, ranch with the 144, two mic stands, two Shure SM57s, a Gibson J-200 acoustic guitar, a few other instruments, some extremely well-crafted and heartfelt songs, and his voice.

Soon, the “demo” part of “demo recording” was rendered irrelevant when Springsteen decided the TEAC 144 tracks possessed a vibe that was absent in the “professionally recorded” E Street Band sessions at the renowned Power Station in New York.

Ultimately, his cassette multitrack production—titled Nebraska—would be released on Columbia Records, reach #3 on the 1982 Billboard Top LPs and Tape chart and score a Platinum Album Award (1 million copies sold) in the United States.

The Boss showed everyone the potential of a homegrown album—as well as establishing a line of success from Nebraska to what is perhaps the current Mount Olympus of home recording, When We All Fall Asleep, Where Do We Go?, recorded in a bedroom studio by Billie Eilish and her brother Finneas.

How Cassette Multitracks Inspired Pro Studio Careers

Seeing an opportunity to establish myself as a local San Francisco songwriter-producer-engineer, I bought a TASCAM 244 around 1982, and hired myself out to record bands in their rehearsal spaces—offering my production services along with my slowly developing audio engineering skills. I recorded a ton of bands and worked that 244 to an early grave in less than four years.

With my 244 teetering on the brink of collapse, I decided to visit Guitar Center to look for a replacement. (Note: The following story is true, although it may sound as if I am giving props to my current employer.) I was always in there—or over at the competition, Don Wehr’s Music City—so the staff was aware of my musical side hustles. I considered breaking the bank by following Bill Nelson’s lead and buying a Fostex A-8 or B-16 reel-to-reel multitrack—as well as the mixer and other accessories that purchase would require—when the salesperson said, “You need to come down to the basement and see what we just got.”

Pictured: TASCAM 234 Rackmount Multitrack Recorder (Rackmount version of TASCAM 244)

Positioned between shelves of guitars was a just-unboxed Studiomaster Studio 4. I was a goner.

With its metal, rather than plastic, chassis, the Studio 4 looked like the big mixers you’d see in pro studios. It had two more mixer channels than my 244 and 3-band EQ. The faders and knobs felt as good as the controls on a Trident Model 16 mixer I had dared to touch during a studio tour when the engineer was putting away his microphones. It was also made in Great Britain, and most of the bands and producers I loved at the time were English.

This was a professional cassette multitrack. I seriously wounded my credit card, but I took it home, and, in my head, I have thanked that Guitar Center associate constantly for helping me upgrade my recording career. The sight of the Studiomaster Studio 4 affected other musicians the same as it did me, and my bookings soared—thanks to the increased audio quality I could deliver with this Brit cassette multitrack.

The TEAC 144 and Studiomaster Studio 4 cassette multitrack were absolutely gateway “drugs” in my studio career. The next stop was opening a pro studio with a friend in an industrial area of San Francisco. Two other professional studios followed. I’m sure other engineers, producers and artists have similar stories. Cassette multitracks made careers …

Pictured: TASCAM Portastudio 424 MkIII Pitch Control and Playhead

Chart of Classic Cassette Multitrack Recorders

It’s not surprising that once musicians realized cassette multitracks allowed them to record demos at home—efficiently, portably and cheaply—they kind of went mad. Everyone had to get one. Immediately. That surge of interest was very good news indeed for TASCAM, and it was also a huge opportunity for other companies. Here’s a chart of some popular cassette multitracks that made the scene during the first big wave of home recording gear in the ’80s and ’90s.

|

Deck |

Debut |

Tracks |

Key Features |

|

TEAC 144 |

1979 |

4 |

Four-channel mixer, four 1/4" mic/line inputs, recording two tracks at a time recommended, Dolby B noise reduction, treble and bass EQ |

|

Fostex 250 |

1981 |

4 |

Four-channel mixer, four 1/4" mic/line inputs, 2-band EQ, Dolby C noise reduction |

|

TASCAM 244 |

1982 |

4 |

Four-channel mixer, four 1/4" mic/line inputs, simultaneous 4-track recording, dbx Type II noise reduction, sweepable midrange EQ |

|

Clarion XD-5500/XA-5500 |

1983 |

|

Four-channel mixer, four 1/4" mic/line inputs, 7-band graphic EQ, onboard echo effect, built-in drum machine |

|

Fostex X-15 |

1983 |

4 |

Two-channel mixer, two 1/4" mic/line inputs, Dolby B noise reduction, treble and bass EQ |

|

TASCAM PORTA ONE |

1984 |

4 |

Four-channel mixer, four 1/4" mic/line inputs, dbx noise reduction, treble and bass EQ |

|

Audio-Technica AT-RMX64 |

1985 |

4 |

Six-channel mixer, six XLR and six 1/4" inputs, 48V phantom power, Dolby B/C noise reduction, 2-band EQ (sweepable) |

|

Vesta Fire MR-1 |

1985 |

4 |

Six-channel mixer, no onboard EQ, six 1/4" mic/line inputs, built-in limiter/compressor (first four channels), dbx noise reduction |

|

Vesta Fire MR-10 |

1986 |

4 |

Two-channel mixer, two 1/4" mic/line inputs, treble and bass EQ, dbx noise reduction |

|

Akai MG614 |

1986 |

4 |

Six-channel mixer, six 1/4" mic/line inputs, two XLR inputs, 2-band EQ (parametric), dbx noise reduction |

|

Studiomaster Studio 4 |

1986 |

4 |

Six-channel mixer, six 1/4" mic/line inputs, six XLR inputs, 3-band EQ (midrange and bass sweepable), Dolby noise reduction |

|

TASCAM PORTA TWO |

1987 |

4 |

Six-channel mixer, six 1/4" mic/line inputs, treble and bass EQ, dbx noise reduction |

|

Vesta Fire MR-30 |

1987 |

4 |

Four-channel mixer, one 1/4" mic/line input, master 3-band graphic EQ, Dolby B noise reduction |

|

Yamaha MT120 |

Late 1980s |

4 |

Four-channel mixer, four 1/4" mic/line inputs, 5-band EQ (stereo bus only), dbx noise reduction |

|

Sansui WS-X1 |

1990 |

6 |

Eight-channel mixer, six 1/4" mic/line inputs, two XLR inputs, treble and bass EQ, onboard digital reverb, Dolby noise reduction |

|

TASCAM 488 |

1991 |

8 |

Eight-channel mixer, 12 1/4" mic/line inputs (eight mono/two stereo), treble and bass EQ, dbx noise reduction |

|

TASCAM 464 |

1992 |

4 |

12-channel mixer, eight 1/4" mic/line inputs, four 1/4" stereo inputs, four XLR inputs, 3-band EQ with sweepable mids (channels 1-4), dbx noise reduction |

|

Yamaha MT8X |

1994 |

8 |

Eight-channel mixer, four 1/4" mic/line inputs, four 1/4" line inputs, 3-band EQ (channels 1-4), 2-band EQ (channels 5-8), dbx noise reduction |

|

TASCAM 424 MkII |

1994 |

4 |

Six-channel mixer, 10 1/4" mic/line inputs, four XLR inputs, 3-band EQ (sweepable mids), dbx noise reduction |

|

TASCAM 414 |

1997 |

4 |

Eight-channel mixer (four mono, two stereo), six 1/4" mic/line inputs (four mono/two stereo), 2-band EQ, dbx noise reduction |

|

Yamaha MT400 |

1990s |

4 |

Eight-channel mixer (four mono, two stereo), eight 1/4" inputs (four mono mic/line, four stereo), 3-band EQ, dbx noise reduction |

|

Yamaha MT3X |

1990s |

4 |

Six-channel mixer, six 1/4" inputs (two mic/line, four line), 2-band EQ, dbx noise reduction |

|

Yamaha MT4X |

1990s |

4 |

Four-channel mixer, four 1/4" mic/line inputs, 3-band EQ, dbx noise reduction |

The Continued Relevance of Hardware Mixer-Multitracks

You may think that in a world filled with DAWs, integrated mixer-multitrack hardware recorders would have gone the way of the dinosaur. They did not. They simply evolved.

TASCAM is still producing Portastudios, such as the TASCAM DP-24SD, but they are now digital machines. The company has even revamped its small-format PORTA ONE cassette multitrack into 6- and 8-track digital Pocketstudios. While not as “porta,” the TASCAM Model 12 is an integrated mixer-recorder offering 12 digital tracks, built-in effects and Bluetooth.

Shop Now: TASCAM DP-24SD 24-Track Digital Portastudio

Although founded in 1983, Zoom opted not to produce cassette multitrack recorders during the product category’s 1980s–1990s heyday. But the company must have been a fan of the concept, as it currently offers compact, digital mixer-recorders, such as the Zoom R12 and Zoom R20.

DAW users can bring some cassette multitrack funkiness to the digital domain with products such as the IK Multimedia T-Racks TASCAM PORTA ONE Plug-in

Shop Now: IK Multimedia T-Racks TASCAM PORTA ONE Plug-in

But even vintage cassette multitracks can still have value in the musicmaking of today—if you happen to be the sonically adventuresome type. Some creators use the mixer section of old decks as preamps to add some brash analog colors to DAW tracks. If I still owned my Studiomaster Studio 4, I’d absolutely do that. The British EQ on that mixer was super intense and beautifully belligerent.

By the way, just in case you think using a cassette multitrack as a preamp is the dumbest dumb idea in a teeming cavalcade of idiotic recording techniques, the JHS Pedals lineup includes the 424 Gain Stage preamp/distortion/overdrive pedal. The 424 Gain Stage accurately recreates the sound of plugging a guitar (or other instrument or vocal mic) into a TASCAM 424 MkI Portstudio—even to the point where the circuit utilizes the UPC4570 and NJM4565 op-amps found in the original recorder-mixer. JHS makes some truly stunning pedals, of course, so can we now agree a cassette multitrack preamp is galaxies away from a daft notion?

Shop Now: JHS 424 Gain Stage Effects Pedal

Here's another idea if you can find a model with its cassette deck in working order. Many cassette multitracks had built-in pitch controls, and you can really have fun mutating sounds by recording or playing back tracks with the tape speed set slower or faster. You get some authentic analog grit and gronk that’s different from digital manipulations—even with tape emulation, lo-fi and/or overdrive plug-ins tossed into the mix.

A small TASCAM PORTA ONE or similar deck could easily fit atop your home-recording desk and act as your secret weapon for blitzkrieging sounds into things of wacky wonder. If you’re intrigued, see if you can get lucky by searching for cassette multitracks in the Recording category of our Used & Vintage shop.

There are two more reasons why the cassette multitrack concept still resonates today. First, think of the limitations of having just four tracks, basic EQ, no signal processing plug-ins, no near-limitless undo functions and none of the other benefits of digital recording.

Pictured: TASCAM Portastudio 424 MkIII Rear I/Os

Trust me, having to make critical creative decision based on what you didn’t have, did not turn home studios into chambers of horrors and regret. Instead, artists were forced to think ahead, make quick artistic decisions (rather than leaving everything until later in the recording process) and determine which elements were essential components of what they were seeking to communicate (instead of throwing a bunch of random ideas into the digital stew). None of these restraints were bad things. We can celebrate the myriad options available to us now, while still recognizing the “forged in fire” beauty of committing to what really counts.

Secondly, a significant number of independent artists and labels are releasing work either solely on analog cassettes, or as bonus options to digital streaming, CDs and LPs. Who knew that cassettes could become one of the coolest things in the age of digital?

Cassette Multitracks and the Triumph of Home Recording

Much like the Greek myth of Prometheus bestowing mere mortals with the gift of fire and knowledge, the cassette multitrack provided musicians with previously unprecedented access to affordable and easy-to-use recording tools. Being able to self-produce tracks without the interference of gatekeepers—or having to struggle to pay for hourly studio time—was an enormous windfall for creators.

I was all in—both as a musician and a music journalist.

As the industry started manufacturing more recording gear oriented to personal studios in the 1990s, the staff of Electronic Musician and I worked tirelessly to upend the status quo and get musicians creating tracks at home. EM’s commitment to the audio uprising was sometimes uncomfortable, as the magazine shared a corporate owner and an office with the bible of the pro studio world, MIX.

Pictured: TASCAM Portastudio 424 MkIII Channel Strips

It also sucked that the emerging popularity of DIY production initiated some downsizing of the big studio industry and the closing of many iconic recording rooms. But big studios certainly aren’t extinct—many of the great ones are flourishing—and the galactic onslaught of creativity unleashed by home studio creators has been a gift to all music lovers.

The first salvo of the greater home studio revolt was fired by the TEAC 144 Portastudio—a device that wasn’t considered much of a threat to professional studio facilities due to its sonic limitations. However, the true superpower of the 144 was in the idea and the opportunity, and the lowly cassette helped change an entire industry.

.jpeg)